Fractured Form: The Influence of Colonialism on Indigenous Carving Styles

Wood carving, in its myriad forms across the globe, often speaks of a culture's soul. It’s a language etched in grain, a testament to tradition, skill, and a deep connection to the natural world. But what happens when that voice is forced to adapt, to alter its tone, its very vocabulary? This is the story of indigenous wood carving styles worldwide, irrevocably shaped by the often-painful legacy of colonialism.

My grandfather, a carpenter by trade, possessed a small collection of antique accordions. Each one was a beautifully crafted instrument, the bellows carefully constructed, the keys worn smooth by countless hands. He’s taught me the respect for craftsmanship, for the years of practice needed to create something of beauty and utility. Looking at these accordions, I see a parallel to the story of wood carving—a history of adaptation, survival, and a quiet resistance expressed through form.

The Pre-Colonial Landscape: A Tapestry of Traditions

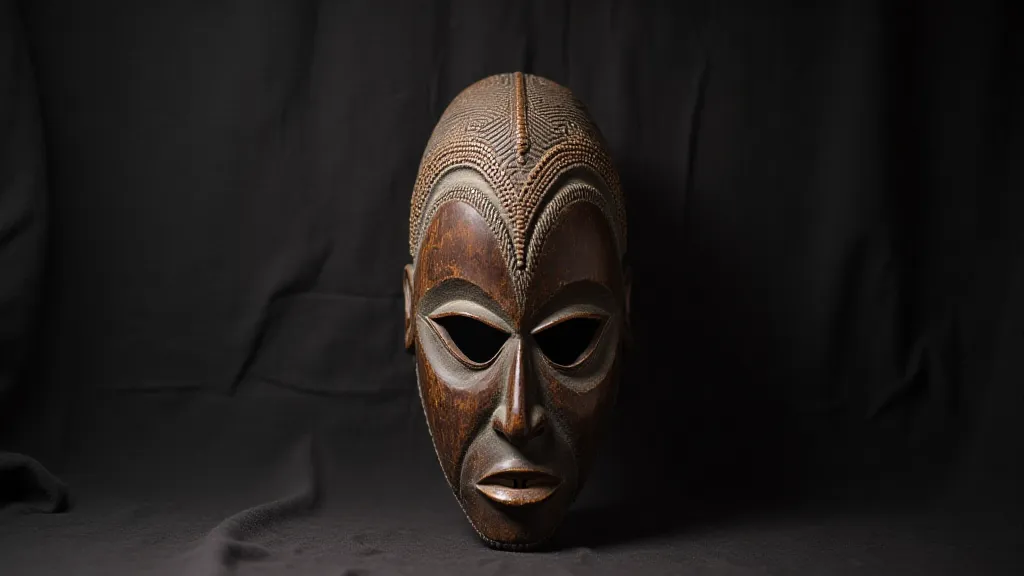

Before colonial intrusion, indigenous carving practices flourished, each region boasting unique styles rooted in spiritual beliefs, clan histories, and the resources available. In the Pacific Northwest of North America, the Haida, Tlingit, and Kwakwaka'wakw peoples crafted towering totem poles depicting ancestral lineage and mythical creatures. The carving involved a profound spiritual connection, with the wood itself considered a sacred entity. In West Africa, the Yoruba of Nigeria created intricate masks for religious ceremonies, each mask embodying a specific Orisha (deity). Similarly, Maori wood carving in New Zealand conveyed ancestral narratives and social status through elaborate panels and meeting house adornments. The materials used—cedar, mahogany, hardwoods, and various types of balsa—reflected the specific ecosystem of each region, and the tools, often made from stone, shell, and bone, testified to a deep understanding of material properties.

The Colonial Shadow: Disruption and Adaptation

The arrival of European colonists marked a profound turning point. The motivations were complex – religious conversion, economic exploitation, and a desire for cultural dominance. Colonizers often viewed indigenous practices as “primitive” or “pagan,” actively suppressing traditional beliefs and artistic expression. Carving, inextricably linked to these beliefs, became a target. In many cases, indigenous carvers were forbidden from creating traditional objects, forced to produce items for the colonial market – often simplified and commercialized versions of their original work. This resulted in the loss of invaluable knowledge, the degradation of sacred symbols, and a deep sense of cultural trauma.

Furthermore, the introduction of European tools – metal axes, saws, and chisels – initially eased the carving process, but also inadvertently led to a shift in techniques. The ability to carve faster and more efficiently resulted in a decrease in the painstaking detail and reverence that had previously characterized the process. The use of imported woods, often cheaper and easier to work with, further altered the aesthetic and durability of carvings.

Themes in Transition: From Spirit to Commerce

The impact on themes was perhaps the most heartbreaking. Traditional carvings often depicted ancestors, spirits, and narratives central to indigenous cosmology. These stories served as a living record of history, morality, and connection to the land. Colonial influence resulted in a gradual shift toward depictions of European figures, animals (often those valued for hunting), and landscapes appealing to colonial tastes. While some carvers subtly maintained elements of their original traditions, often cloaked in symbolic imagery, the overt expression of indigenous beliefs was often curtailed.

Consider the Maori carvings. Initially depicting ancestral figures and mythological creatures, the carvings gradually began to incorporate European motifs - ships, buildings, and portraits of colonial officials. While some Maori carvers brilliantly adapted these foreign elements, blending them with traditional techniques to create a unique hybrid style, it underscored the pressure to conform to colonial aesthetics. The ability to subtly maintain elements of their original traditions became a form of silent protest, a defiant assertion of identity in the face of oppression.

The Resilience of Form: A Legacy of Subversion

Despite the profound disruption, indigenous carving traditions haven’t vanished. They’s evolved, adapted, and in many cases, undergone a resurgence in recent decades. The post-colonial era has witnessed a renewed appreciation for indigenous cultures and a concerted effort to reclaim lost knowledge and revitalize traditional practices. Carvers are revisiting ancestral techniques, incorporating traditional themes, and using native materials to create works that honor their heritage.

In some cases, this revival involves reimagining traditional forms in contemporary contexts. For instance, some contemporary indigenous artists are using carving to address social and political issues, using the language of their ancestors to speak truth to power. The creation of carvings become acts of defiance, affirmations of cultural identity, and vital expressions of resistance.

Collecting and Appreciation: A Deeper Understanding

For those interested in collecting indigenous carvings, it’s crucial to approach the endeavor with sensitivity and respect. Understanding the historical context is paramount. Recognizing the impact of colonialism on the carving process allows for a deeper appreciation of the art form—an acknowledgment of both the pain and the resilience embedded within each piece.

Furthermore, supporting contemporary indigenous artists is a crucial way to ensure the continuation of these traditions. Purchasing directly from artists or reputable galleries that prioritize ethical sourcing practices helps to sustain livelihoods and empower communities.

A Continuing Conversation

The story of indigenous carving styles is a complex and deeply moving one. It’s a testament to the enduring power of human creativity and the indomitable spirit of indigenous communities. It's a reminder that art is not merely about aesthetics—it’s about history, identity, and the ongoing struggle for cultural survival. The lines between the past and the present are blurred, and as we examine these fractured forms, we glimpse the echoes of colonialism and the burgeoning promise of a renewed cultural voice.